A guide for writing fact extractors for Datalog

Today's post is a guide on how you can prepare and model a dataset in a straight-forward and scalable way for use in Datalog. As you will see, most things are not all that different compared to how you model data in SQL, but sometimes there's a little twist involved. Let's dive in!

Create a dedicated "fact extractor"

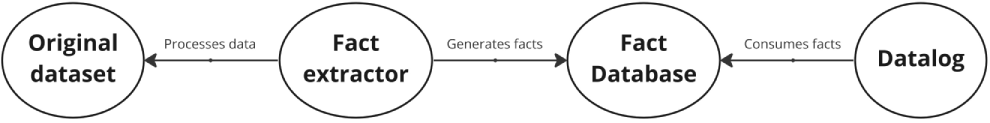

Datalog can be a powerful tool when you need to work with deeply connected data, but most Datalog implementations require the data to be in a specific format (Datalog facts). This means that you will need to write a so-called "fact extractor" that extracts Datalog facts from your starting dataset.

The extractor can be a direct part of a larger application, or it can be a completely separate application that focuses only on processing data. This will most likely depend on a couple of things:

- Do you need a specialized tool or library only available in a certain language?

- Can the data be stored or cached somewhere in between fact extraction and the actual processing in Datalog?

- Are there performance requirements that need to be met?

- Any other application requirements?

A separate fact extractor is more flexible since you can use any language / tool to extract the facts, but in general it's best to write the extractor in the same language as the main application (if possible). This reduces the amount of overhead other developers will have working with your Datalog-powered app or library.

Keep your fact extractor simple

While staying on the topic of mental overhead, keep your fact extractor as simple as possible! Only put as much logic in the extractor as you need for generating the Datalog facts. As long as the essential data is in there, Datalog could always be used to compute other, more complex derived data.

Doing this means you will most likely only need to change the extractor rarely, and you can focus on the more important logic written in Datalog.

Extract everything

When trying to first analyze a dataset, it's not always clear what exactly you are looking for. For this reason, you should extract as much useful information as possible from the data. This gives you the freedom to experiment and iterate on a solution in Datalog. If you find at some later point you are generating data that isn't being used, then you can always remove it again from the extractor code.

One type of information = one fact type

You should create a new type of fact for each distinct part of information in your original dataset (just like you would in SQL). This will make it trivial to transform the original source data into Datalog facts.

And just like in SQL, it's advised to add a unique identifier to each type of fact. This will make it easy to refer to a specific fact value in Datalog queries. A unique ID can be as simple as an integer value in the extractor that is incremented after each emitted fact.

A simple example of this would be a fact for storing information about a person. A combination of first and last name might not be unique, but by adding a "id" column, we could distinguish that they are different people.

A unique ID is not only useful for referring to values: if you are using Datalog embedded in another language, it will also make it easy to retrieve certain information by ID from Datalog back into the host language.

Link your data using unique IDs

If you followed the advice from the previous section, all your main fact types should now have unique identifiers. Besides your main fact types, it can be valuable to create facts for relations between the data. And because we have assigned unique IDs to each of them, this makes it easy to link the different parts of data together.

The term "relation" can be thought of in a very broad way here. It could be e.g. the posts made by a user on a blog, or if you have a value that contains many other values. This can be useful for some Datalogs where you don't have support for lists of variable length.

An example of this is for example during program analysis where you want to analyze a program and you would encode parts of the program as Datalog facts. Here's how you could encode a small program containing a function call:

This could be translated to the following Datalog code:

.decl function_call(id: unsigned, name: symbol)

.decl literal_number(id: unsigned, value: number)

.decl literal_string(id: unsigned, value: symbol)

// Here we link an argument in the function call to the actual function call:

.decl function_call_argument(function_call_id: unsigned,

argument_position: unsigned, value_id: unsigned)

function_call(0, "myFunction").

literal_number(1, 123).

literal_string(2, "abc").

function_call_argument(0, 0, 1).

function_call_argument(0, 1, 2).In the snippet above, a fact type was created for both of the literal types, and for function calls. A helper fact type was also created that links the function arguments to a specific function call via the unique identifier.

Optimize the fact generation only if you need to

When working with a dataset for some time, you might notice certain access patterns of data that are done many times in a Datalog analysis. If these patterns contribute to a significant portion of the total analysis time, you might consider changing the extractor to emit additional specialized facts for this purpose.

Note that this should only be used as a last resort when you already optimized your Datalog code, since this technique can quickly introduce a lot of complexity in the extractor. In general, it's better to keep the extractor simple (as mentioned earlier)!

Build logic on top of the generated facts

When you finish writing your fact extractor, you are now ready to start using the data in Datalog! If you followed all the previous steps, you should have a good basis for writing complex queries and logic on top of all these facts!

Conclusion

In this article, I gave some recommendations how you can prepare and model your data for analysis in Datalog. If you want to see a "real world" example where these suggestions are being used, take a look at the semantic analysis in my Eclair compiler.

If you think I missed any important steps in this guide, let me know! I will add a section credited to you. 😄

If you are interested in more content like this, follow me on Twitter. Feel free to contact me if you have any questions or comments about this topic.