How to lower an IR?

In today's article, I show the approach I use when writing a compiler to lower one intermediary representation into another. I will be using Haskell to explain how to do it, but this technique can be used in other languages as well (with some minor modifications). Since this is a very general and broad topic, it will be hard at times to go into specifics but I will try to mention the key things that are applicable every time.

So what is "lowering" anyway?

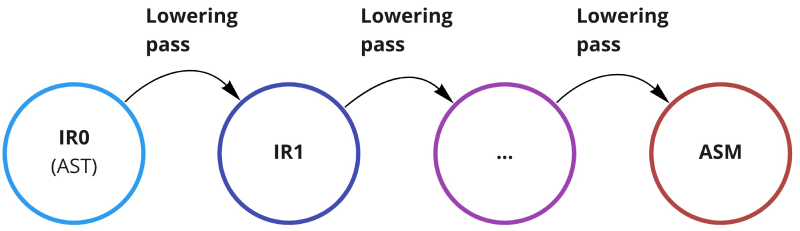

Before we dive into the code, let's first take a look at what a typical compiler looks like. In essence, a compiler reads in one or more files, parses them and transforms the contents into executable code. This transformation often ends up being quite involved and is performed in multiple steps to manage the overall complexity. A single one of these steps is often called a (lowering) pass.

Between each step of the compilation process, a different IR or intermediary representation is used to gradually remove high level features and describe them in terms of lower level features. Do this enough times, and eventually you will end up with an IR simple enough to be compiled down to the assembly level.

Writing a lowering pass

With the introduction out of the way, we can now start writing an actual compiler lowering pass. Let's first create 2 simple IRs:

-- IR1 is a calculator-like language that only supports addition

data IR1

= Number Int

| Plus IR1 IR1

example :: IR1

example =

Number 31 `Plus` Number 10 `Plus` Number 1

-- IR2 is a stack-based language

data IR2

= Block [IR2]

| Push Int

| AddThe IRs are kept simple to prevent this article from exploding in size, but they are complex enough to show the ideas behind lowering an IR. With the IRs out of the way, we can now implement our pass. In Haskell, the simplest type signature for a pass would look like this:

This should be easy to implement, right? A function that takes one argument (an intermediary format) and transform it into another format. However, most of the time, there are factors making this much more complicated:

- The IR datastructures tend to be sum types (tagged/discriminated unions) with many different variants, that each need to be processed differently.

- To perform the transformation, you often end up needing a lot of additional information, not immediately available at that point in the IR tree.

- Some of these transformations might require a lot of logic (which might in turn require some internal state to be managed).

- Higher level features in one IR might need to be mapped to a combination of multiple constructs in the lower level IR.

All these things combined quickly turn that simple function into a complex beast. To deal with this complexity, we need a structured approach. I usually like to split my code into two modules (next to my module defining the IR):

Codegen.hs forms a module that contains helper types / functions / combinators for doing the actual code generation. This module usually also defines a CodegenM monad that keeps track of state during the compiler pass. Since all helper functionality is defined in Codegen.hs, Lower.hs contains only the high-level logic to transform one IR into the next.

This might seem a little abstract right now, so let's see what it would look like for the 2 IRs defined earlier!

-- NOTE: Since our example is so trivial, we could simply implement

-- it like below. This simple implementation might be useful to keep

-- in the back while going through the second approach:

lowerSimple :: IR1 -> IR2

lowerSimple = \case

Number x ->

Push x

Plus x y ->

Block [lowerSimple x, lowerSimple y, Add]

-- For a more complex/realistic scenario this won't be enough,

-- so let's apply the strategy discussed previously:

-- in Codegen.hs:

import Control.Monad.State

import qualified Data.DList as DList

import Data.DList (DList)

-- First we define a Monad that keeps track of emitted instructions

-- during lowering.

newtype CodegenM a

= CodegenM (State (DList IR2) a)

deriving (Functor, Applicative, Monad, MonadState (DList IR2))

via State (DList IR2)

-- This executes the monadic action, and returns the final internal state.

runCodegen :: CodegenM a -> [IR2]

runCodegen (CodegenM m) =

DList.toList $ execState m mempty

-- A helper function to emit an instruction

emitInstr :: IR2 -> CodegenM ()

emitInstr instr =

modify (\instrs -> DList.snoc instrs instr)

-- OR: modify (flip DList.snoc instr)

-- And helper functions for the push and add instructions:

push :: Int -> CodegenM ()

push x =

emitInstr $ Push x

add :: CodegenM ()

add =

emitInstr $ Add

-- and now we can implemnent the lowering pass in Lower.hs:

loweringPass :: IR1 -> IR2

loweringPass ir1 =

Block $ runCodegen (go ir1)

where

go :: IR1 -> CodegenM ()

go = \case

Number x ->

push x

Plus x y -> do

-- NOTE: compared to `lowerSimple`, we no longer need to emit an

-- additional `Block` in this case.

go x

go y

addLower.hs now contains a function loweringPass :: IR1 -> IR2 that performs the lowering of the IR. It delegates to a monadic go function, which does a pattern match and recursively handles all cases of the IR on a high level, while all details are handled by the CodegenM monad and combinators. This is close to what we initially wanted to write!

We can quickly check to see if the lowering pass works:

-- A quick-and-dirty interpreter for the stack-based language:

interpret :: IR2 -> Int

interpret prog =

execState (go prog) [] !! resultIndex

where

resultIndex = 0

go = \case

Block instrs ->

traverse_ go instrs

Push x ->

modify (x:)

Add ->

modify $ \(x:y:rest) -> ((x + y) : rest)

main :: IO ()

main = do

-- The next line prints: "Block [Block [Push 31,Push 10,Add],Push 1,Add]"

print $ lowerSimple example

-- The following line outputs: "Block [Push 31,Push 10,Add,Push 1,Add]"

print $ loweringPass example

-- And the final 2 lines print "42".

print $ interpret $ lower example

print $ interpret $ loweringPass exampleCode generation of recursive structures

While the previous approach works well enough for this simple example, sometimes you also run into situations where you need to emit recursive structures. With a few tweaks to our previous solution, we can also support this feature in a fairly straight-forward way:

-- NOTE: There is no need to manage state manage by the monad now,

-- but in a real example this could still be possible.

newtype CodegenM a

= CodegenM (Identity a)

deriving (Functor, Applicative, Monad)

via Identity

runCodegen :: CodegenM a -> a

runCodegen (CodegenM m) =

runIdentity m

-- A Block can be thought of as the recursive structure in our example.

block :: [CodegenM IR2] -> CodegenM IR2

block ms = do

irNodes <- sequence ms

pure $ Block irNodes

-- If you wanted to, you could even flatten the structure too.

block' :: [CodegenM IR2] -> CodegenM IR2

block' ms = do

irNodes <- sequence ms

pure $ Block $ flip concatMap irNodes $ \case

Block instrs -> instrs

instr -> [instr]

-- `push` and `add` now return their corresponding IR nodes

-- If needed, you could also use the internal state of the monad

-- to do more sophisticated code generation here.

push :: Int -> CodegenM IR2

push x =

pure $ Push x

add :: CodegenM IR2

add =

pure Add

loweringPass' :: IR1 -> IR2

loweringPass' ir =

runCodegen (go ir)

where

go :: IR1 -> CodegenM IR2

go = \case

Number x ->

push x

Plus a b ->

-- Replace with block' to flatten the IR

block

[ go a

, go b

, add

]The key idea in the above snippet is how the block combinator works: it takes a list of monadic actions that will return IR2 nodes when evaluated. This allows you to perform any effects you need in a controlled way in each of the other combinators that generate IR nodes.

(Thanks to Reddit user /u/philh for pointing out this part was missing!)

Final thoughts

In this post, I explained how I structure my compiler to transform one intermediary format to another format. By using a two-module approach, the internal details stay separate from the high logic, giving a clear overview of what the transformation is doing. Even though transforming an IR always results in different challenges, this general technique should always be applicable.

Besides the techniques I described in this article, here are some final tips that also make writing lowering passes much easier:

- Don't try to cram everything into one pass. Splitting up a transformation in two (or more) parts can be a great way to reduce complexity, increase maintainability and improve testability.

- The

recursion-schemeslibrary in Haskell can help with structuring the many moving parts of a lowering pass (though it comes with a learning curve). My previous blogpost showed how to create recursion-schemes using comonads, which I ended up using in several of my compiler's passes.

You can find some more complex examples in my Eclair Datalog compiler here and here (look for the Codegen.hs and Lower.hs modules). Note that these examples are much more complicated than the toy example presented in this post, as is usually the case with compilers 😅.

If you have any questions or thoughts about this topic, let me know on Twitter.